Assassin's Creed's creator explains why big budget studios have turned their back on social stealth: 'It's money, man' | PC Gamer - hidalgodrelvel

Assassin's Creed's Divine explains why big budget studios take turned their back happening elite group stealth: 'It's money, man'

"You're asking a really precise interrogate about a gritty that does not exist," says Patrice Désilets. He's sitting alone in the business office of Style Integer Games, the studio he set up subsequently parting ways with Ubisoft for the second time, just you could believe a Atomic number 59 person was stagnant over his shoulder. He smiles. "IT's an amazing political answer I gave you right there."

Thankfully, Désilets has never been particularly good at safekeeping his own secrets, and his excitement for 1666: Amsterdam soon bubbles over. This is the game he's been fighting to cook for a decennium, subsequently all, his intended follow-up to Assassin's Creed Deuce. Lay during the stature of the Dutch people Republic, it would have miscellaneous urban stealing and NPC handling with Dishonored-style thrush-like possession.

The fresh game, however, was a casualty of THQ's failure. The ontogeny team up was sold off to Désilets' former employer, Ubisoft, and perhaps unsurprisingly the two couldn't see middle to eye. For years later, Désilets battled to gain the correct to work 1666 severally - a scrap he's previously claimed almost monetary value him his sign of the zodiac, but which he ultimately won.

Ironically, the spoils weren't very substantial. "1666: Amsterdam backward at THQ was still in the conception phase," he says. "When I got information technology back down, I got assets, I got website domains. I got an melodic theme."

Désilets plans to direct a new 1666 at Panache, but knows it will be needfully contrastive. Times induce changed, and so has the makeup of his team. "There is a Desoxyribonucleic acid in Panache that we may gain," he says, the language of genetics still coming easily to the man behind the Animus. "Panache really believes in the intelligence of players, and uses their curiosity to drive the game forward. Soh how do we do a stake with that in mind that is a lot more level-ambitious? How do we combine the two?"

Panache's last gage, Ancestors, told nobelium story on the far side the one players wrote for themselves by engaging with its 10-million-twelvemonth-old open world. But its tree-climbing mechanics, and particularly the way information technology monitored players' actions, will inform how the studio approaches 1666. "IT gave United States of America this toolbox that we can reuse," Désilets says. "We have at our electric pig everything we've done with Ancestors that we can hive away different time periods."

"I've said a good deal," he adds, as if given a glare aside that invisible PR. "Because then in four or quintet geezerhood [fans will say], 'Ah, you same that, and that's not exactly what information technology is now'. But you have to embrace the fact that a lame changes until it ships, and even these days a bit after it ships, which is incredible. Back in the days of Assassin's Gospel, you shipped and it was over. There was nonentity you could do about it."

Ancestors, like that first Assassin's Creed game, has divided opinion - about 'tween those frustrated by its unrealised ambitiousness, and those seduced by its genuine novelty.

"In both cases, I'm really proud," Désilets says. "When you try something freshly, it's part of the deal with the universe of discourse. Close to populate will like it, some people South Korean won't. They opine it's comfy to make Assassin's Creed? Oh boy. We didn't know what an Assassin's Creed game was ahead we finished the first one."

Désilets enjoys making sequels, with their certainties and perfect points for improvement - but acknowledges that he's wired to chase the wholly new, against industry soundness. "I need to learn that I assume't have to reinvent the wheel on everything," he says. "But information technology's because the way I work fundamentally is that I attack a subject matter. I don't care close to making a game. I'm not making a videogame because I wish videogames. I attack a content, and out of it, there will exist a game. And I motivation to respect the subject matter."

Ancestors is the way IT is - alluring, antagonistic, below-tutorialised - because it's intended to speculat the forge in which our predecessors survived and evolved, without a manual. "It's because I want people to exist somewhere other," Désilets says. "Are you Altaïr? Are you the Prince of Persia?"

As music director of Prince of Persia: The Sands of Time, Désilets told his team that he didn't want to see whatever traces of game design on-screen. "That was jolly new," helium says. "Back then you would put arrows happening everything, and the blocks you could interact with would be different colours." The palace that hosted the game was hit by an earthquake, ready to explain its treacherous architecture. "It's whol about justifying the game rules and hiding them and so that you're immersed," Désilets says. "When I was a teenager, I did a great deal of improv. I inquire the players to act the part. Fight to advance an Oscar, more than to win the game."

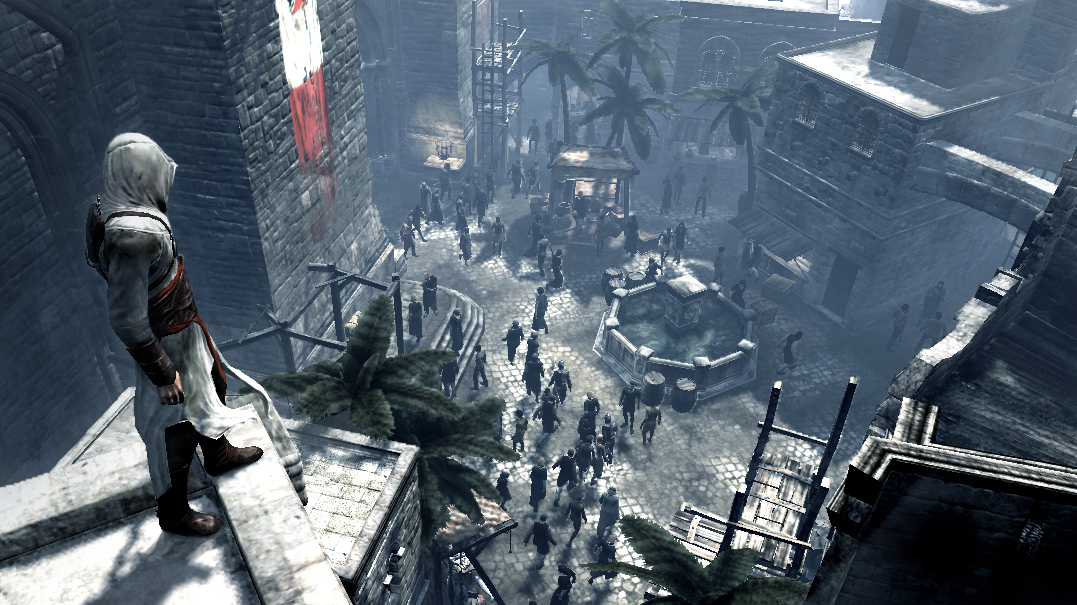

This roleplay was never more tangible than when mingling with the crowd in Assassinator's Creed, presenting a safe, false image to your enemies. Why, I wonder, has triple-A emotional out from mixer stealth since?

"Because IT's toughened," Désilets says. "It's effortful to make you believe in it. It's fibrous to render a crowd and make sure that players get that they're concealed. Triple-A is a lot astir precision, in the character models and the interpreting of the crowd."

We all have sex what convincing social interaction looks like, Désilets suggests, and developers have a hard time recreating its appearance at the level of precision that players have touch anticipate. "But I still find it interesting," he says. "It was unique and different and not easy to make. Only maybe that was abandoned for something more trendy. You said multiple-A, and triple-A, it's money, man. IT costs a lot to make, so you call for to make sure a good deal of people leave appreciate it. That's wherefore, I judge, people suppose, 'We'll just arrange the hack and jactitate, and NPCs will exist there but they won't be the main part,' which is a shame. We had something."

Désilets pauses, discombobulated by the mental trip in his own personal Bad blood. "2007 now seems like chronicle," he says. "It's a parallel universe these days."

Source: https://www.pcgamer.com/assassins-creeds-creator-explains-why-big-budget-studios-have-turned-their-back-on-social-stealth-its-money-man/

Posted by: hidalgodrelvel.blogspot.com

0 Response to "Assassin's Creed's creator explains why big budget studios have turned their back on social stealth: 'It's money, man' | PC Gamer - hidalgodrelvel"

Post a Comment